While Armenia has been described in a centuries-old poem as ‘the paradise land, the cradle of humankind,’ the Eurasian country – situated just outside the Fertile Crescent and Levant – might appear far enough off the beaten path to suggest a dearth of significant literature or a lack of notable literary figures. However, Armenia stands poised to astonish casual observers and the uninformed with its formidable, contemporary writers and vast wealth of ancient poetry and historical literary works.

Those, who lived amid the Cold War, glasnost, and the eventual crumbling of the Soviet Union, might very well seem like living relics to some younger creative types in Eastern Europe and Western Asia. Enjoying a level of artistic freedom of which their grandparents could have only dreamed, certain Armenian writers and artists are garnering attention both within and outside the confines of their homeland. One such writer is Elfik Zohrabyan, who recently discussed his life as an author, playwright, actor and educator in Vanadzor, a city located in the north of Armenia. He eagerly expounds on the current state of Armenian literature and expresses optimism regarding its future:

GREG FREEMAN: With a long list of plays, short stories, fairy tales and satires to your credit, Elfik, you have garnered both academic acclaim and the attention of avid readers (as evidenced by several interviews on television) and the inclusion of your work in prominent anthologies. Tell me more about your writing interests and objectives.

ELFIK ZOHRABYAN: In art and in literature, I’m interested in the mystery and essence of a human being. Plays and prose can show a person from different sides. Literature can’t change the world, but it can influence it. I wish to create literature that can influence people and give the reader an aesthetic pleasure. Vivid uniqueness. This is what I wish to have as an author.

G.F.: What are some of your more notable works?

E.Z.: The judge of literature is the reader. My creations may be praised by talented readers but I am nearly always displeased with myself. As English speaking readers don’t know many of my plays or short stories yet, it’s not clever to speak about them. However, I can mention my works are not only about Armenians. I write about human beings from everywhere and about the problems of today’s person. One of my monodramas will soon appear in Georgian and Persian anthologies.

G.F.: What direction is literature taking in Armenia?

E.Z.: Now one can notice almost all types of writing styles and literary tastes in Armenia. The interesting fact is that nearly all of them are very different. Armenian poetry has its very high place in the context of world literature. Now there are new artistic forms, styles and looks in Armenian prose and plays.

G.F.: Having lived much of your life in post-Communist Armenia, have you observed significant changes in the world of Armenian writing and publishing?

E.Z.: We know that in the Soviet era not every work was allowed to be published, but readers were many, and a fresh work would become the target of discussions. Now it seems that there is indifference to arts in general. Many scholars guessed the time of global decadence would come, but [I believe] that notable works in the arts will always be appreciated. Now you can find every sort of writing, and everyone can publish a book, but publishing is on a very high level in Armenia.

G.F.: Are outside influences, particularly those of the West, a good thing?

E.Z.: In the arts, mutual influences are somewhat necessary. Armenian culture has always had its great influence in the world’s culture. For instance, Artavazd Peleshyan has influenced the world of film directing, particularly in the field of documentaries. And it’s natural that outside influences will [affect] Armenian culture, too. Influence is a good thing if it motivates you to find yourself. Shakespeare, Márquez, Faulkner, Kafka, Borges, Hesse, Aytmatov, Camus, many Russian writers and others have influenced Armenian literature, but there are no epigones here.

G.F.: William Saroyan was obviously one of the most notable members of the Armenian diaspora. How has his work affected you?

E.Z.: Saroyan won an Oscar, the Pulitzer Prize and other awards. Saroyan has influenced Kerouac, Salinger and others. He didn’t like to follow any rules in literature. He did as his heart dictated. His eccentricities have influenced me. Though writing plays has its rules, ignoring them may break the structure and rhythm, causing plays to become material for reading. Plays don’t die if they are performed.

G.F.: Recently you published There’s Something I’ve Got to Tell You: A Collection of Five Saroyan Plays. Tell me how you came to translate these works. Was it especially gratifying to be backed by the Ministry of Culture on this project?

E.Z.: I wrote a thesis about Saroyan’s short plays, and this academic study helped me in translating. Saroyan’s plays are often considered experimental. The Armenian stage needs short and experimental plays. So this motivated me to translate five short plays by him. One of them has already been performed. The translations must have a high quality in order to secure backing by the Ministry of Culture in Armenia. The book was supported by the Ministry because Saroyan was one of the greatest writers in the world. Now I am going to translate other English language plays into Armenian.

G.F.: In addition to Saroyan, which writers or works have impacted you?

E.Z.: Oscar Wilde, Anton Chekhov, and Samuel Beckett influenced me much, but especially Wilde. One is influenced by a favorite writer in whose creation he finds the features which may exist in his own works and in his own style. And the basic influence of my creations was Armenian national literature, though I partially follow our national literature’s “traditions.” Waiting for Godot impressed me much. I used to dislike absurd drama because of its gloomy colors. Now I have changed my viewpoints.

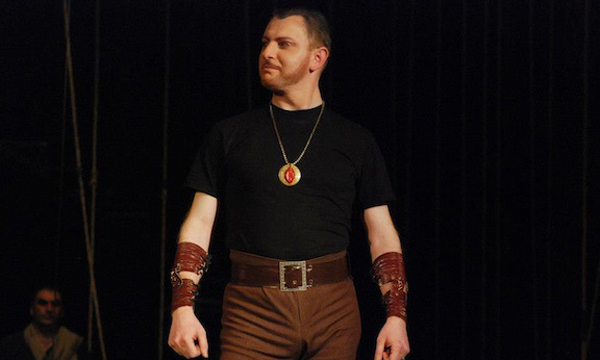

G.F.: As an actor, you were awarded the Gold Medal by Armenia’s theatrical union? Tell me more about that honor.

E.Z.: When an artist has much to say, he may [employ] different forms of expression. Since the age of fifteen, I have worked at a state theatre named after Armenian national actor Hovhannes Abelyan. Our theatre is over eighty-years-old. Acting helps me to write plays professionally. History shows that playwrights who had true success also played on the stage. Studying theories and watching various performances are not enough to become a playwright. As to the medal you mentioned, for me the titles, prizes, and awards are relative. Though they may stimulate an artist to create without disappointment and to feel appreciated, one should give attention to both the awards and [constructive] criticism. However, I thank the Theatre Workers’ Union of Armenia for this honor.

G.F.: Is it true that you are a fan of Shakespeare? What are some of your favorite Shakespearean plays? What roles have you enjoyed playing the most?

E.Z.: Shakespeare is more than the wealth of England. His work is close to Armenian hearts, too. Our professional groups have performed his plays since around 1865. He was known in Armenia far earlier. For instance, one of the prominent figures of the Armenian national liberation movement, Hovsep Emin, asked his friend in a letter to give his “deep honors and greetings” to one of the best Shakespearean actors, David Garrick, who was the director of the English theatre, Drury Lane. Hamlet, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, and Othello are my favorites. My secret dream was to play one of the major Shakespearean roles, and fortune smiled on me twice. I have already played Tybalt and the Duke of Cornwall. Those roles enriched me much. At Vanadzor State Theatre, King Lear was performed, and it was a very unique rendition among the Shakespearean performances. Directed by Vahe Shahverdyan, nearly all of the characters were acted in new ways. In King Lear and Romeo and Juliet, I always played so differently in every performance, enjoying the roles more than any other ones. And we should not forget Armenia’s great actor, Vahram Papazyan, who was one of the top portrayers of Othello in the twentieth century, having played that role more than 2,000 times.

G.F.: What are your own plays generally about? Are they historical or contemporary in context?

E.Z.: I started to write plays around thirteen or fourteen after watching the performance of Three Sisters by Chekhov. Two of the actresses inspired me so much. All of my plays are very different from each other. They seem to be by different authors. I pay attention mostly to the modern person, drawing from people’s problems, inner feelings, and relationships with others, often using irony and sharp humor. One of my monodramas is about classic actress Siranuysh, who was considered Armenia’s Sarah Bernhardt. One of her biggest problems was the passing of the so-called live performance. The stage actor lives on only in the memory of the audience. My last play is an absurd drama.

G.F.: Wasn’t one of your plays performed in Karabakh?

E.Z.: Yes, one of my fairy tale plays was well-performed in Karabakh (Artsakh). That play was performed in our state theatre, too. Both performances were unique and interesting. Kharabakh’s group even took part in a theatrical festival and won first place. I’m happy that Kharabakh’s Armenians don’t stop performing interesting plays and have continued creating.

G.F.: From Saroyan to Tennessee Williams, you have an insatiable appetite for British and American literature and plays. Do others share your enthusiasm?

E.Z.: Sure, I myself especially like Nobel Prize-winning writers, and plays by Shakespeare, Williams and Eugene O’Neill are often performed in Armenia.

G.F.: As a teacher, how are you nurturing the creativity of young people? Have a number of your students gone on to pursue acting or writing?

E.Z.: I am the head of a dramatic studio where there are two courses, and I also work at the Vanadzor branch of the Yerevan State Institute of Theatre and Cinematography where I teach Theory of Drama, Basis of Playwriting and English (from ABC). The students are my wealth. Sometimes I am surprised at how well they remember my teaching in detail. My students enter universities and often study tuition-free because of their high grades. Some of them become winners in the Republic recitation contests, often receiving the highest awards. I learn from them, also.

G.F.: As one of the more rapidly developing countries of the former Soviet Union, is Armenia in a position to produce some of the greater writers of the region?

E.Z.: Armenia is in the process of producing some of the greatest writers of the region of modern times, though Georgia also has modern talents.

G.F.: With a history of strained diplomatic relations between neighbours Turkey (because of its reluctance to officially acknowledge the Armenian Genocide of 1915) and Azerbaijan, what positive role do you think a new generation of Armenian writers could play in bringing people together in peace?

E.Z.: Nowadays, Turkish and Armenian artists often communicate. Writers, actors, and musicians meet. I have some Turkish pen pals, who recognize the Armenian Genocide and hope that morality and justice will prevail against diplomatic egoism. I can assure you that no young writer or artist in Armenia wants war with Azerbaijan. In our theatre repertory, there is even a performance in which Armenians and Azeris are shown to be friends until an awful war destroys everything. I want Azerbaijan’s young writers to not refuse to be published in anthologies containing Armenians and Georgians. I would also like to see an end come to the burning of books by Azeri writer, Akram Aylisli, who wrote positively about peace-loving Armenians and showed a mirror before the face of his dear homeland. We should remember we live once, and it is unwise to enjoy aggression. I wish bright days of peace to the people of Caucasia and to the world!