Chapter 5 Hangestatsav – Found Peace

Chapter 5 Hangestatsav – Found Peace

Hripsimeh’s Story, Tehran, Iran, 5th January 1920

Hripsimeh rose before it was light and lit the portable paraffin stove, took it to warm the bedroom where the children were sleeping. They had been in Tehran for just five years but they had come a long way in more ways than one. Arriving practically destitute and traumatised by the journey, grieving for their home and the brother they’d left behind, they had been taken in by distant cousins, Assyrian relatives on their mother’s side. Hripsimeh took comfort in the everyday routine of looking after three demanding children; it was the only thing that seemed to set her mind at rest. She would lose herself in the simple task of sweeping the floor and then washing it, on her hands and knees; took small nuggets of satisfaction in shaking out the mat, in cooking: the cutting, slicing, shaking, stirring, frying, baking – the repetition of putting breakfast, lunch and dinner on the table; in the physicality of doing the laundry, the washing, scrubbing, wringing out. In the clean fresh smell of laundry put out to dry, the gathering in, the folding and putting away. These helped to keep the haunting faces and eyes at bay, the memory of the stench bodies rotting by the roadside, the children abandoned, orphaned, starving. It had taken every ounce of strength they had possessed to bring the three children, Artoosh, Souren and Louise, with them. Artoosh, the eldest at eight walked the whole way, though at times he would slump and refuse to go any further. Pleading and tears were the only thing that got him going again, his feet a mass of bursting, oozing blisters. His cousins were two years younger and the adults had had to carry them most of the way. When it got too bad for Hripsimeh, Israel had put one child on his shoulders and another on his hip.

After a year of sleeping on other people’s floors, Israel managed to save enough money to be able to rent their own place – he had always had a gift for tinkering, an enquiring mind and determination to get to grips with how things worked, how they were put together. Despite his illiteracy, his services were slowly, increasingly in demand as the country moved towards mechanisation and since Mozaffaredin Shah had just imported the first car, a Ford, from Belgium, it was all the rage. His future, their future felt hopeful, the promise of more secure work on the horizon. They managed to rent two rooms on the first floor of an old house, occupied by seven other families. After a couple of years, they had expanded to three rooms on the same floor – two used as bedrooms, one for the children and one for Israel. Hripsimeh made herself comfortable in the sitting room, rolling out a mattress once the children were tucked up and the day’s work done. She found being in a city was a blessing, the crowds, the noise, the chaos could swallow you in, help to make you invisible. Nevertheless, she was always on her guard, never drew attention to herself and her children, obeyed the rules of segregation, repugnant though they were to her.

The boys, Artoosh her son and Souren, her nephew were still sound asleep. Her niece Louise turned over and moaned: “Oh God, do we have to go to school today Hripsikmamajan?” The child had always called her ‘mother’; she was the only mother she had ever known. Having lost both parents when she was three, she had no tangible memory of them. She spoke to her aunt in Caldean, her dead father’s native Assyrian tongue. She had also inherited his passionate, jealous temper – Hripsimeh was sure the child had fire in her veins instead of blood.

Hripsimeh stood for a moment, with her arms folded and looked warily at her niece. She sniffed, went off to the kitchen and came back with a spoonful of sticky, fragrant honey, a chunk of the wax honeycomb still attached. The girl snatched the spoon greedily from her and stuffed it into her mouth, feeling the warmth of the sweetness melt and trickle down her throat. “Come on now”, said Hripsimeh, unmoved, “no exceptions. Shake yourself my girl or you’ll be late for school”.

Today was their Christmas eve, tomorrow Christmas day, Jurokhnek when her community traditionally celebrated the nativity and Christ’s baptism. The children were excited and school was the last thing on their minds. Tonight there would be feasting to look forward to and later, midnight mass. Hripsimeh had been fasting all this week in preparation, she was devout in her faith, no meat, milk or eggs had passed her lips for seven days. She would break her fast tonight. In the meantime, she would give the children a treat.

Her brother was already stirring. Israel dressed hastily, gave her a peck on the cheek. “Shnorhavor soorp tsenoont, happy holy baptism”, he said, catching her by the shoulders. Her eyes welled up with tears. “Our brother should be here, with us”, she whispered, “where in God’s name is he Israel, why did he stay behind? It was foolishness, we knew what was coming, we saw what they were doing, we saw with our own eyes! You should have made him come. He’s dead, I know he is,” she said softly, her head bowed, her quiet tears soaking into his shirt. “Hushush”, he soothed, there’s no good to come of going over it. Come Hripsik koorikjan, sister dear, the children will be hungry, we need to get them to school.

Israel grabbed his everyday jacket which hung on the back of the door. “One of each please, Sangak and Barbari!” called his sister, gulping back tears and wiping her eyes with her apron. “Back soon!” he replied cheerily. He knew she loved the coarseness of the Sangak bread, it was certainly more of an acquired taste, made of brown wheat flour, stones thrown onto the dough in the clay oven, giving it its characteristic pockmarked surface. He and the children preferred the doughy white of the Barbari.

She shook the boys awake one-by-one, they rolled over and stretched out languidly. Artoosh reached for his glasses – since they had come to Tehran, they had realised he was chronically shortsighted, had grown increasingly so. It saddened her to see his handsome face framed by the thick heavy frames, but he didn’t seem to mind, his studies had improved exponentially since he began wearing them. The boy had shown a gift for languages in particular. As well as his native Armenian he had grown up fluent in the same languages as his mother: Farsi, Caldean, Russian and Turkish. At Jean d’Arc, the French school run by the holy fathers and nuns, where he and his cousins were given free places because of their orphaned status, he soaked up yet another. Hripsimeh was sure he would have gone into diplomacy as his grandfather had done, but was unsure of his prospects here in Tehran. Unlike the prosperous, well-established community in Isfahan, the smaller Armenian community in the capital were eyed with suspicion by the local Muslims, who saw the Christians, as well as the Jews and Bahai’s as Najes, unclean.

Hripsimeh busied herself in the kitchen, set the table with a mismatch of plates and cutlery, bits and pieces she’d picked up at the market. She put out the butter then pulled the chalky-white goats cheese out of the brine and set it on a plate of its own. Taking four large eggs, she broke each one and separated the gloopy white from the orange yolks, setting the whites to one side to use in the kookoo, the herb cake, for their Christmas feast later. She took a handful of the sugar lumps she’d hacked from the sugar dome she’d bought last week (the children sat around as she chiselled away at it, grabbing the nuggets of compacted sugar powder hidden in its depths, released by her hammer blows and stuffing them into their mouths) and put them in the stone bowl. She crushed them to powder with the mortar and put the sugar dust in with the yolks. Taking a large fork, she began to beat the mixture, a constant, patient rhythm that in the time it took for her brother to return from the bakers, transformed the egg yolks from orange to bright yellow, to pale yellow to creamy white.

Israel came blustering in through the front door, a cold wind blowing in behind him, two hot steaming loaves of bread, tucked under his arms. The warm doughy smells brought the children running. “Bah, bah! Yum!” They exclaimed, as Hripsimeh set the bowl of Gogli, the egg mixture in the middle. “Merci, Mamajan”, Artoosh smiled, tearing chunks out of the barbari bread and dipping it into the egg. “Well, it is Christmas Eve, after all”, said his mother, pouring black tea for all of them. Only when they were all noisily engrossed in their meal – only then taking a small handful of the Sangak bread. Chewing slowly on her meagre breakfast, she only had eyes for her son, watching his every move as he poured his tea into his saucer and took a piece of sugar from the bowl. First blowing onto the amber liquid, he popped the sugar into his mouth, clenched it between his teeth and noisily slurped the hot liquid down. Louise pulled a face, the doting love her aunt displayed for her son was more than she could bear. “Eh! That’s disgusting!” she blurted, “You’re an animal!” Souren chewed slowly and quietly, watching his cousins, his gaze detached. ” Anshnork, how rude!” snapped her aunt, irritated. The girl jumped up, offended: “Its not fair!” she screamed, “he always takes the best bit of barbari, gets to eat most of the gogli and he slurps and burps and we have to listen to it all!” Grabbing a large handful of bread she turned on her heel – the child would rise to any reprimand, she was getting harder to control by the day – woe betide her cousins if they picked an argument with her, they would always come off worse. She snatched up her schoolbag and huffily took her coat from her aunt who followed her out as she practically ran out of the door, slamming it hard behind her.

“Good riddance!” exclaimed her aunt under her breath. She truly loved the girl but she made life maddeningly difficult for all of them. They all breathed a sigh of relief and continued their breakfast in peace and quiet.

Later, Hripsimeh pulled the obligatory chador over her headscarf, and took her shopping bag from the back of the door. It was freezing cold and she hurried to the market, stood patiently to one side of the stall waiting to be served. She watched the local Muslim women go about their business as they squeezed the fruit, smelt bunches of herbs, rubbing the leaves between finger and thumb and chatted, exchanging pleasantries with the shopkeeper and each other. When at last he had served everyone and there was no one else he could put before her, he at last made fleeting eye contact and gestured to her to show him what she wanted. She pointed to various bunches of herbs, parsley, dill, tarragon and mint, then spring onions and eggs. That would do for the kookoo. He gestured for her bag. She opened it and he dropped the groceries in, careful not to make any physical contact with her. He was happy enough to take her money from her hand, she noticed, as she put the coins into his open palm, no change forthcoming. She walked away with a wry smile, thinking she was sure he would not put himself to the trouble of washing that!

Back home, she carefully soaked the herbs in fresh water, spreading them out on clean cloths to drain, putting the mint, tarragon and a few spring onions to one side for eating later, with their meal. She would use the rest: holding the bunches with one hand over to keep them from straggling out, she chopped with the other, her steady pace and sharp knife gradually reducing the green mounds, the house filling with herb-fresh fragrance. She put the raw egg whites left over from the morning breakfast into a large bowl and added another ten eggs, beating them to a froth. Pouring the eggs onto the herbs, she gently combined them together then folded in no more than a couple of tablespoons of flour, gently. She finished with a generous sprinking of salt and pepper – a swift dip of her finger and the slightest flick of her tongue confirmed that the seasoning was just right.

Two large spoonfuls of lard, melted slowly in the deep pan on the stove. When the fat began to spit, she quickly poured in the egg and herb mixture and covered the top. She would brown the top later, when it was set. The fish had been rinsed of its salt and she wrapped it in a paper parcel and baked it with a little butter and dill. The rice had been soaked overnight and she, parboiled it, rinsed it and put it on to dam, to steam, adding the chamich, raisins which puffed up and glistened in the intense heat.

When the children came home from school, she got them to scrub up and change quickly into their best clothes. When at last her brother came home, they were ready. The kookoo, a majestic herb cake was set in the middle of the table, surrounded by the chamich plav, rice with raisins, the salted fish and jajik home-made yogurt with herbs. The house smelt of Jurokhnek, of Christmas. Israel pulled a bottle of red wine out of his pocket and his sister, delighted, ran to get the corkscrew. “Where on earth did you get hold of it?” she asked. He winked his eye and tapped his nose at her. The Armenians were traditionally merchants after all. It was expensive, but worth it, for this most special night of the year. They all sat down together and waited patiently as their uncle poured a small glass each for the children, just to taste, and a larger glass for his sister and himself.

“Yerekherk, children, this is our most treasured time – we have this precious life and we have each other.” his blue-green eyes welled up and his voice caught. He cleared his throat and continued with more determination. “Be minded of what you have rather than what you have not. Shnorhavor Jurokhnek, Shnorhavor soorp dznoont!” Hripsimeh held her breath, trying to keep her sobs at bay. She didn’t want to spoil this moment, but she knew, she could never forget. She stuffed her handkerchief into her mouth and bit on it and gradually, the noise of happy, chattering children and the clatter of cutlery on plates distracted her and eased the ache in her heart.

The year to follow was a momentous one. On the 21 February 1921, Reza Shah an obscure Cossack officer of peasant parentage overthrew Ahmad Shah Qajar, the last Shah of the Qajar dynasty, staging a coup d’etat, a military dictatorship that began a twenty year reign of terror that tolerated no opposition. The Islamic veil was abolished and brutally enforced with soldiers ordered to pull the chadors, the sheets of fabric off women in the street.

Louise’s Story, Tehran, November 1967

The funeral cortege drove in slow motion, winding its way down the narrow streets of south Tehran, amidst anarchic, death defying traffic; the line of cars wound itself around Jaleh Square, jamming the roads and bringing the streets to a standstill until, sluggishly, reluctantly, the way opened up, little by little by little and the hearse found its way, to the Catholic cemetery. The family car followed it to the gates and parked close to the yellow brick walls. Another twenty cars parked behind, in front, higgledy piggledy wherever they could find a space.

Artoosh and Clara emerged from the first car, smart black suits, sombre; Artoosh, shoulders shaking as he wept. He had visibly aged since his mother’s death, the light and life seemed to have been sucked out of him – she had been his light, his life. He walked slowly behind his mother’s coffin, his hat in his hands, vulnerable; his prematurely bald head shiny, glasses misted over. He blew his nose loudly, not caring. The girls, Lolo, Diane and Lily followed with their husbands; behind were the cousins, uncles, aunts and friends, the women’s faces bare of makeup, red rimmed eyes, knotted handkerchiefs.

The coffin was set down by the side of the open grave and all stood solemnly, heads down, hands clasped together as the priest led the prayers and began the burial service. A commotion at the back started quietly, gained in momentum – jostling and shouts: “Let me through, please let me through for pity’s sake!”

The familiar face burst out of the crowd and the family looked up, visibly shocked at the disturbance. “Oh God, its Louise”, whispered Clara to her husband who had begun to get agitated, confused at the sudden imposition in their private grief. Artoosh looked into the woman’s eyes, wild and red raw with weeping, nose running, hair unkempt. She looked insane, but it was, unmistakably, his cousin.

“Artooshaber, brother Artoosh!” she screamed, “Es incha! What is this? Mames merela! My mama has died, God help me! I didn’t make my peace with her, didn’t speak to her for thirty years! Oh God, what stupidity! I have a pain in my heart, in my head, it won’t go away! Her face is there when I close my eyes, I can’t sleep, I can’t eat! I have to beg her forgiveness, I beg your forgiveness! Astvadzim! My God, she was the only mother I have ever known! How could I repay that? I repaid her with snubs and silence! Help me please, or I will die with this burden!”

She flung herself at the coffin, scrabbling at the catches – “I must see you, Mamajan, one last time – please, please let me see her, one last time, Artooshjan, khuntroomem, aghachoomem, please, I beg you!”

The crowd were agitated; faces shocked, voices low, dismayed. How could she do this, come here, make such a scene, ask such a thing? Unspeakable.

Artoosh kneeled by his cousin, put his hand on her shoulder: “Louise, lav, gbatsenk, ok, we’ll open it”, he turned to Clara whose face showed utter disbelief, “let her see her one last time, what harm will it do? She has gone from us, she is in peace”.

The priest gestured for the coffin to be opened and as the lid was lifted, Louise threw herself on Hripsimeh, her arms around the lifeless corpse, hands cupping the hollow face, showering her with kisses and heaving with gasping, choking sobs. The crowd looked away, Artoosh wept openly, Clara put her arms around him. The priest, stepped forward and to everyone’s relief, knelt by Louise, gently lifted her up and led her away.

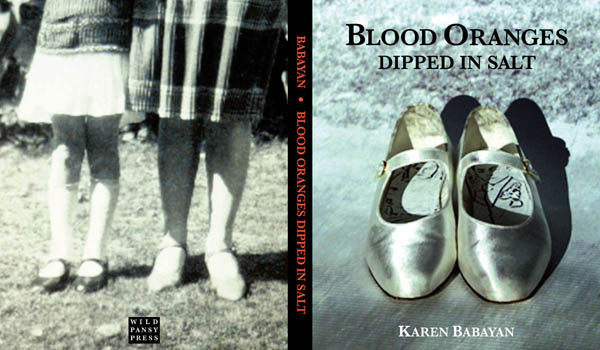

Babayan, Karen, Blood Oranges Dipped in Salt

Published by The Wild Pansy Press 2012

ISBN 978-1-900687-40-9

Web address for the book

1 comment

Վարուժ Սուրէնեան | Կարմիր նարինջներ թաթախիած աղի մէջ | Գրանիշ says:

Apr 10, 2014

[…] Կարեն Բաբայանի գրքից մի հատված կարող եք կարդալ այստեղ […]